“It is just an illusion we have here on Earth that one moment follows another one, like beads on a string, and that once a moment is gone it is gone forever. When a Tralfamadorian sees a corpse, all he thinks is that the dead person is in a bad condition in that particular moment, but that the same person is just fine in plenty of other moments. Now, when I myself hear that somebody is dead, I simply shrug and say what the Tralfamadorians say about dead people, which is ‘so it goes.’”

-Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse Five

It’s crazy how four years is everything in the moment but just a dot in the past once it fades away. There was the last time I slept in class, the final time I ate a peanut butter cream cheese jelly bagel from Sage, and a termination of Taco Tuesdays. I didn’t know how final they would be at the moment, but they’re touchable only by Tralfamodorians now.

Freshman year was the sleep before the dream. Sophomore year was the wake-up call. Junior year came in like a lion, sugar blossoms on the tree of my identity. And senior year felt like a popsicle, short and sweet and sliding past my senses. These four years melted in my mind; they were cream cheese jelly sweet, each bite of memory tinged with a smile; they were popsicle sweet, my body icing over every embarrassing incident; and they were syrupy sweet, leaving marks on my fingers no matter how hard I try to brush it off.

My four years at Delbarton. like any lefe-experience, had its ups and downs. In the end, though, I think it was all right. That it was always all right. And it’s alright at the end as well. It’s hard to see clearly in the thick of it. In the fog of war, in the dark night, I sometimes lost hope of finding a star. But looking back, I don’t think I would change a thing. I am all right at this moment. To a Tralfamadorian, I always will be.

Act 1

“At first, you love something for all the ways they’re perfect. But after a while, you love it for all its flaws.”

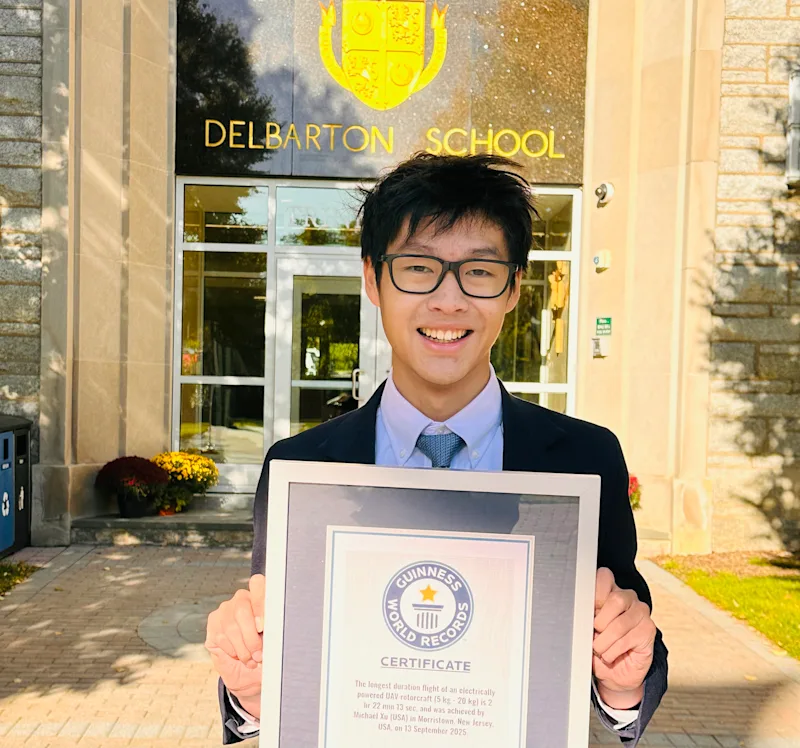

From the orientation speech to the posters plastered around the school to the lifers who could already preach Delbarton culture, brotherhood echoed like a propaganda poster. I admired Delbarton’s reputation as an elite prep school, partially excited and partially intimidated to compete with the best minds New Jersey had to offer. From the Gatsby-esque eloquence of Old Main to the tastefully done statues and fallen pillars, I came under the impression that I was entering a new haven of arts and culture, a microcosm of the Renaissance. Feeling the cherry blossoms twinkle over tumbling hills and reading about the superb programs, I was swayed into joining Delbarton’s ranks. The twelve Bloomberg Terminals, the Steinway piano in a practice room, and the collection of widgets in the Science Wing radiated grandiosity and opportunity. I had an idealized vision of Delbarton and thought of all the ways it was perfect for me.

Then, I got there.

Ninth grade came in the middle of Covid. Walking up the steps to Trinity Hall, I felt waves of apprehension as sure as the autumn leaves fell. I fell into the old cliché of not knowing where to go. It took a while to understand how to decipher the symbols on my class schedule into buildings/classrooms and then where they were actually located.

On the first day of school, I sat at my desk, not saying a word. I’d been an introvert my entire life. Next to the lifers who already knew each other and the naturally outgoing kids, I felt barely connected in this community that emphasized inclusion. With a bag of blank notebooks and an equally blank stare, I walked past a sea of masks into classrooms bathed in Kleenex wipes and hand sanitizer. With my breath masked in annoyance and perspiration clouding my glasses, I found common ground with other students over the neglected child of isolation and desolation, COVID-19.

My adjustment to Delbarton took time. Here, I was a racial and religious minority. I was an introvert in a classroom that rewarded extroversion. I’d made friends over similar interests, classes, and a distaste for Covid-19, but I still felt misplaced in the wider Delbarton community. That’s not to mention the status of freshman year itself as a transition. Course rigor increased, the size and scale of everything jumped, the social environment became more complex, and the stress of college admissions took root.

I think everyone likes to think about the alternate lives they could have had if they had done things differently. One of those parallel paths was if I’d gone to Seton Hall Prep; from my small Catholic middle school, most of my friends matriculated there. I was the only one lost in transit to Delbarton. What would my life be like if I had chosen to be a pirate, or someone else? In my exploration phase at Delbarton, these thoughts came naturally with the uncertainty of reality, my well-being, and the future. When I performed poorly on a test or got beat out by a rival, I wondered if I would have done better at Prep, where the classes are easier, and the GPAs are higher (at least anecdotally). When I felt lonely and disconnected from the Delbarton community, I wondered if I’d have had a better time with friends I’d known for years instead of months.

By this time, though, I was in full motion, and no roadblock could stop me from doing my best on assignments, gorging on Sage dining, and joining clubs (I fondly remember starting the Coding Club). More importantly, I was fortunate enough to meet many kind and delightful individuals at Delbarton, who redefined a more personal, intimate community for me.

In my teachers, I found comfort in Father Demetrius’s unorthodox teaching approach and sense of humor. He juxtaposed discussion of Jujitsu next to Ancient Eastern Monasticism, and occasionally brought up his gun collection. Mr. Carlisle and Mr. Theroux, on the other hand, were more like military leaders: tough but fair. Few days passed without complaining about a history assignment or a biology lab. Through their classes, I soon found partners in my peers: sharing notes, creating Quizlets, and hopping on late-night study calls.

A senior at the time – Will Li – emailed me with a brief introduction and a few recommendations for activities. Through this guide, I wandered the fine arts center and met the jazz ensemble – a suggestion based on my previous experience with the piano. Although I didn’t pursue jazz further at Delbarton, it did influence my decision to play in Mr. Lyman’s band the next year. The warm welcome set the tone for what my time at Delbarton would be like – kindness and an exploration of interests.

Likewise, our school has school-spirit groups called “Deaneries.” Within these groups, students could learn and listen from the group leaders and compete in schoolwide events. During my first deanery session, a junior dean came up to me and asked what game I was playing. I wasn’t any good at conversation, so I just muttered a few words under my breath. I thought he would go away, but he continued to prod about my skills, scores, and interests unrelentingly. By the end, I realized two things: Junior deans are the most forgiving and persistent people on the planet, and I found a best friend in mine. He made my time at Delbarton twice as meaningful, and I wouldn’t trade it for anything in the world. Having served as both a junior and senior dean these past two years, I hope I left behind something similar to those below me.

While my initial excitement with Delbarton mellowed, I found a middle ground in my relationship with the school. I still saw my shadow reflecting differences with the ground beneath, but I also saw the unique beauty present in the campus and the people across it. I still occasionally mused about alternate lives, but I accepted my current path as the best possible timeline I could have. I don’t regret my decision to come to Delbarton at all. And that, I suppose, is the best love story I can tell.

Act 2

“I was a victim of a series of accidents, as are we all.”

During this time, I grappled with my identity, my expectations, my reality. The older I got, the harsher the competition for respect and understanding, and the thinner my skeleton became. I often wondered… is my excessive desire for an identity due to A) ignorance, B) the restrictions of a boy’s social circle, C) parental and peer pressure to be someone special, or D) all of the above.

When I was young, every essay I wrote about myself ended like this: bite-sized synopsis, good morals with lessons learned, and characters coming to terms with one-line epiphanies. But the truth is, my search for an identity never came together in one satisfying conclusion. I could only grasp pieces of myself in experiences as I sent my thoughts into the night.

Ironically, the common thread I found through all the pieces of myself was separation. The separation of my interests, the separation of my body, and the separation of my beliefs and experiences defined me. For example, my interests span both STEM and the humanities. My room is lined with research posters and stacked with sonnets with a fractal-themed calendar hanging from the shelf. The future is a stream of diverging probabilities, and each path feels like a riptide tempting my curiosity. Whether I give a talk on number theory or absurdism, I believe my conversations live on in the hearts of the audience. Whether I’m cutting through stanzas or an equation on A4 graph paper, I indulge in the joy of movement.

At Delbarton, I learned about God’s omnipresence, “omni” coming from the Latin root for “all.” This ability intrigued me. Even though God is one being, He could be everywhere and in everything. Through God, I saw my own omnipresence and what it meant to be part of a whole. My strands of hair strewn across the kitchen floor after a haircut. The grass clippings after I mow the lawn. The friends I made in China, and the bicycle helmet I lost in Yosemite National Park are all parts I left of myself. The world is within me, and my identity is divided across it. Through separation, I am bilingual, multicultural, and omni-inquisitive.

The essay of my life doesn’t fold into a neat conclusion. My search for identity didn’t conclude at Delbarton, and maybe it never will. The dichotomies in my life—STEM and humanities, solitude and community, introspection and outreach—are not contradictions but harmonies.

I am a kaleidoscope, collecting and dancing with the threads of light around me. I am more than the sum of my parts.

Act 3

“To ask what college is for is to ask what life is for, what society is for—what people are for.”

Starting in December, the line between expectation and reality wrapped around my neck as the release of college decisions approached. I felt a tangled feeling of helplessness amidst a shortage of breath. My feet felt stuck in glue, broken as a broken recorder that a broken rage won’t fix.

And then, the dream I’d chased for half my life, the screaming baby of jealousy and self-hatred, happened: I got into college. At the moment, I didn’t know whom to tell. My teachers shined. My classmates awed. My rivals languished, or as I would like to imagine. I felt excited, relieved, exuberant, tired, empowered, proud, and euphoric: I had won.

But that finish line wasn’t the end. I could feel the excitement at that moment, yet I could also feel how rare it was. A few days later, the initial excitement faded, and I felt empty. I’d finished every objective in this videogame I had set up for myself, yet I wanted to play more. When school wifi wanes, my computer becomes a frozen shell, fitting an eternity into one tab switch. My body felt the same way, scripts and to-do lists falling into nothing, no matter how many times I refreshed. Grades sunk, paralysis set, gods cried. Stickers and college merch didn’t help much.

Through high school, I found myself caught between two selves. On one side, I wanted to fit in and be like everyone else. On the other side, I had the selfish desire to be loved and loved alone. The culture formulated in my household and at Delbarton was designed to produce excellence, no matter the means. Appearing at the top of rankings, blazing through every subject, and seeing my room filled with medals and certificates felt like the natural state of the world. Any deviation felt like I was flailing in quicksand.

That selfish desire ate up how I spent my days and what I thought about at night. I used 3 am mornings to find solace and escape in the only time I felt I truly had for myself. Pain, pride, desire, and frustration seared like lightning in my heart, and my appreciation and love for the beauty of others fled as a shooting star. Childhood became a ladder I needed to climb. With each step came height, maturity, experience, achievement, and people. But every ascent equated with another loss: innocence, simplicity, joy, and the enthusiastic naiveté with which I used to chase after everything.

I remember the first poem I ever wrote: the darkness of my room, illuminated only by a small desk lamp and the stars outside my window. I had been sitting there for hours, hunched over loose-leaf paper with a pen in hand, eager to create something new. Gradually, I began entering work into competitions. It felt fulfilling to let my work be seen and be resonated with by strangers. The validation and joy that came along with qualifying for unique opportunities were unparalleled, and the comments I received from relatives and family friends uplifted me.

Yet, thinking back, I realized that at some point in my teenage years, my motivation to create poetry became warped. It was no longer about what brought me fulfillment but instead about honor and pride. There is a scientific term for this. It’s called the “overjustification effect”. The overjustification effect is a cognitive bias that occurs when an external incentive reduces a person’s intrinsic motivation to perform a task. This effect can cause people to lose interest in activities they used to enjoy. More specifically, my intrinsic motivation for writing had been replaced with the external motivation for validation.

So, for the past few months, I have contemplated the reason behind everything. How did I pick up art in the first place? What does art bring me? And why do I still do it?

This period is a time of soul-searching for me. One book I found particularly fascinating was Excellent Sheep, a commentary on the absurdity and madness that fuels the ascent into higher education. Moreover, it touches on the motivation to study the liberal arts in the first place. To quote, “art is the transmutation of the daily bread of experience into the radiant body of everlasting life. It’s the incessant labor of combining your own experience, taken in and metabolized by intense feeling and thought, with what you have acquired in books. Art and life, back and forth, each illuminating the other, both together creating a self.”

I still do innately enjoy the craft of writing. It brings me joy to watch ideas evolve on paper, and the attainable expressiveness is greatly inspiring. Writing, in itself, is a method of self-exploration. With each additional piece, I could understand more about my inner thoughts and feelings.

I still don’t have answers to many of the questions I have, nor any idea of what next year or next month holds. However, I have come to believe that college should be a place where I can continue my exploration of myself without fear of criticism. I don’t have a clear answer, but I think the Dead Poets Society put it pretty well: “We don’t read and write poetry because it’s cute. We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion. And medicine, law, business, engineering, these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for.”

Epilogue

High school really ends on a random Wednesday afternoon. In a way, this ending is the price we pay to attend Delbarton.

Right now, I’m reminiscing about friends and the forested paths I ran in freshman year cross country. I’m wondering how long it’ll take for the school to erase my footsteps. Outside is dusk and solace, but I know now I couldn’t be a star without the night surrounding me.

Delbarton provided me with a vantage point on elite education, self-identity, and the craft of art. These hallways are laced with my memories, hopes, and dreams. I won’t remember what I wrote on the AP Physics C test, but the person I am now is formed by the knowledge I’ve studied and their resultant ideas. I have left behind countless versions of myself in classrooms. I’m sure every teacher and student has a different version of me in their mind. I do, too, but the search for who I am will never end. We all want to be loved, but I never found happiness by chasing success. I think it’s found by the hard work you put into pursuing such a dream.

Even though any veneer of perfection has long faded, I’ve learned to appreciate not just the majesty of the senior garden but the quiet moments of understanding shared with a teacher, the laughter that cuts a sterile air of anxiety, and the communal striving towards excellence, flawed yet sincere.

For everything, I’d like to thank my teachers, my peers, my friends, and the staff. I’d like the thank The Courier and Mr. Wyatt. I’d like to thank Delbarton.

“What more could I want now beyond everything I’ve ever had, all over again?” – -Christopher Buckley