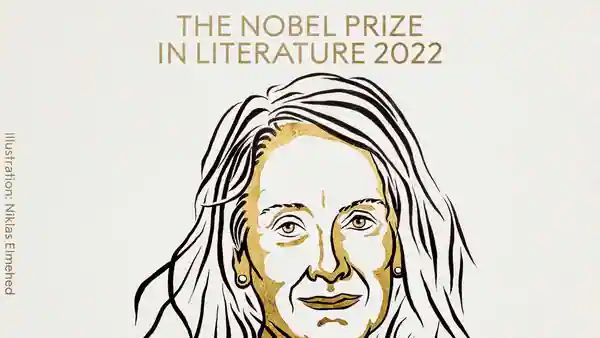

Nobel Prize for Literature

Annie Ernaux Takes Top Literature Prize

November 1, 2022

French novelist Annie Ernaux received the Nobel Prize in Literature on October 7th “for the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory.” Ernaux, not widely known outside of France, has been praised for her autobiographical and sociological novels such as Happening and The Years.

Other writers considered to be in contention were Kenyan author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Norwegian author Karl Ove Knausgård, and Czech writer Milan Kundera. However, we will not know the true list of nominees until fifty years after the announcement of the awards.

Ernaux is a unique voice, a subdued and specific record of the private consciousness that recalls both Woolf and Proust (though that latter comparison may just be a side effect of her Frenchness). Her register is austere, yet able to capture both the surface and subterranean elements of life; her life, in particular. The memoir is her medium.

The criteria by which the Academy selects the laureate is by no means objective, and the idea of 18 Swedish elders choosing the best writers in the world seems, on its face, absurd. Despite an idealized vision of apolitical selection based solely upon aesthetic merits, the Nobel Prize in Literature inevitably carries political weight, and an effort to diversify selection outside of the Anglophone world—the United States specifically. In the literary community, many speculated on whether Salman Rushdie would finally receive his flowers in a tacit statement by the Academy for free expression and against dogmatism. Others wondered whether the award would be gifted to a Ukrainian writer—Oksana Zabuzhko, perhaps—as a statement on Russia’s brutal war. However, the Swedish Academy has always tended towards safer options, and the extent of their political ambition seems to be diverse and equal representation between language, nationality, genre, and gender.

They’re not very good at it. The Academy has, in the last decade, recognized five women (an unprecedented equal split), but only two non-Europeans and three non-white writers. And, as if to balance out any equitable intentions they might’ve had, they awarded the 2018 Nobel Prize in Literature to a conservative genocide denier and a progressive feminist at the same time. (Talk about mixed signals!)

While these intentions are admirable, especially given the permeation of Eurocentric and misogynist thinking in Western literary institutions, they’ve kneecapped the award’s prestige, when obviously great writers (Pynchon, McCarthy, DeLillo, etc) remain unrecognized due to their American nationality, and the laureates of the last three years, while revolutionary and experimental in their own way, are still considered “safe” according to the criteria of the Academy. There are women and non-white authors whose selections would represent a risk to the academy’s narrow view of aesthetic merit: Anne Carson and Can Xue are two prominent examples. Ernaux’s novels, the well-written work of a practiced craftswoman, nevertheless will not cause the literary world to shake, and this is how the Academy would like it—perhaps they regret the commotion regarding their selection of Bob Dylan in 2016. Ernaux herself is a political radical and a leftist, though this has gone strangely underreported in the weeks following the award.

The reaction among writers and commentators has been, at most, a shrug, and further proof of a relatively recent joke: Who’ll win the Nobel Prize in Literature? Someone you’ve never heard of.